- Ohio History in 2000 Words

- Mound Builders

- Native Ohioans

- The Ohio Company

- Ohio's Wood Forts

- Indian Wars

- War of 1812

- Ohio's Canals

- Ohio's Road

- Scenic Railroads / Museums

- Underground Railroad

- Civil War in Ohio

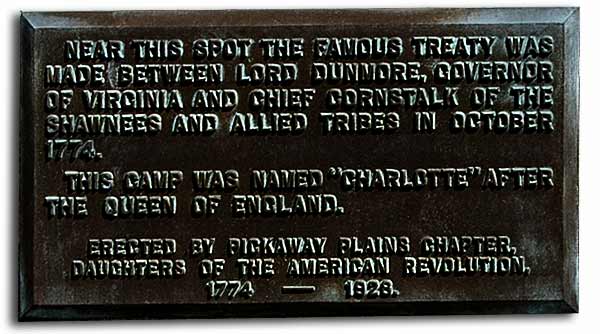

Historical monument and marker near where the treaty of Camp Charlotte was made between Lord Dunmore and Chief Cornstalk.

Shortly before the Revolutionary War began, hostilities were increasing on the western frontier in what is now Ohio and Kentucky. Settlers, who had been outlawed from moving north of the Ohio River, ignored that prohibition which had been imposed in 1763 by the British government.

During this time there were a number of factors that involved different people with different goals and allegiences. Open hostilities between patriots and the British in come of the 13 colonies were heating up. The unrest made it more desirable for some folks to try and escape the dust-ups that were happening with more frequency.

When these folks decided to move, they heard about the new Kentucky and Ohio Territories.

Some pioneers at that time held little regard for British rule, and held even less regard for the Native Americans in Ohio. The settlers began laying claim to land on the north side of the Ohio in direct opposition to the British proclaimation. These incursions resulted in numerous conflicts between pioneers and Native Americans in southern Ohio and retaliations across the river into Kentucky.

In an effort to maintain peace with Native Americans, the British imposed the Proclamation Line of 1763, which prohibited colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. Some settlers did not recognize British authority and continued to move westward. Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore, realizing that peace with Native Americans was improbable, amassed troops and headed west, camping on the Hocking River to meet with a unit under Andrew Lewis. En route, on October 10, 1774, Lewis's troops were attacked at present day Point Pleasant, West Virginia, by Delaware and Shawnee Indians led by Cornstalk. After intense battle, the Indians retreated back across the Ohio River to villages on the Pickaway Plains. Lord Dunmore headed to the Shawnee villages to make peace and set up Camp Charlotte at this site. The Treaty of Camp Charlotte ended Lord Dunmore's war with the Indians and stipulated that they give up rights to land south of the Ohio River and allow boats to travel undisturbed.

White settlers, many from Virginia, ignored the treaties from the beginning. Thousands crossed the Appalachians and lesser numbers pushed beyond the Ohio. Clashes between the races became increasingly frequent. In May 1774, eleven Mingos were killed in a confrontation near present-day Steubenville, Ohio; included among the dead were the father, brother and sister of Logan, a Mingo chief. Many natives in the area wanted full-scale war against the white intruders, but the Shawnee chieftain Cornstalk resisted.

Logan sought out the perpetrators of the killings and led an attack into western Pennsylvania. Thirteen whites were killed during the foray, prompting the British commander at Fort Pitt to stage counterattacks against a series of Mingo villages.

The governor of Virginia at this time was John Murray, the fourth earl of Dunmore. Lord Dunmore had served in the House of Lords prior to a brief stint as governor of New York. Dunmore was a staunch supporter of the Crown and on three occasions closed down the Virginia legislature as a means to dampen patriot enthusiasm.

Dunmore's decision to inject himself into frontier warfare has been the subject of considerable speculation. Some have argued that he was concerned about the growing number of Pennsylvanians crossing the mountains into the west and wanted to advance the claims of Virginians. Others have maintained that Dunmore was totally self-serving and was simply trying to open the west for his own speculative ventures.

The governor prepared a two-pronged offensive, one directed against the natives in the Kentucky (present-day West Virginia) area; the other, led by Lord Dunmore himself, marched toward Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania.

The defining event of Lord Dunmore's War occurred under the leadership of Andrew Lewis, who led his force into the Little Kanawha valley. The presence of a British force in native lands convinced Cornstalk that he should discard his moderation and form a large war party. In the Battle of Point Pleasant (October 10, 1774), the Shawnee were defeated and forced northward to the villages across the Ohio River.

The Shawnee, Mingo and Delaware later signed the Treaty of Camp Charlotte (near present-day Chillicothe, Ohio), in which they pledged to allow free navigation on the Ohio River, to return all captives and release their claims to the lands south and east of the Ohio (the first time that the actual residents of the area had made such an agreement).

By the middle of 1775, Lord Dunmore had managed to alienate all of Virginia. In June, he took his family and fled to the safety of a British warship, which he thereafter judged to be the seat of government. On November 7, 1775, Dunmore issued a proclamation offering freedom to slaves and indentured servants who would leave their rebellious masters and fight for the Crown. The appeal did not meet with success and Dunmore soon returned to England to resume his seat in the House of Lords.

Cornstalk's murder

Cornstalk's commanding presence often made quite an impression upon American colonists. One Virginia officer wrote of Cornstalk at Camp Charlotte: "I have heard the first orators in Virginia, Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee, but never have I heard one whose powers of delivery surpassed those of Cornstalk on that occasion."

American Revolution

With the coming of the American Revolutionary War, Cornstalk worked to keep the Shawnee nation neutral, representing his people at treaty councils at Fort Pitt in 1775 and 1776, the first Indian treaties negotiated by the nascent United States. However, many Shawnees hoped to take advantage of the war and use British aid to reclaim lands lost to the Americans. By the winter of 1776, the Shawnee were effectively divided into a neutral faction led by Cornstalk, and militant bands led by men such as Blue Jacket.

Murder

In the fall of 1777, Cornstalk made a diplomatic visit to Fort Randolph, an American fort at present-day Point Pleasant, seeking as always to maintain his faction's neutrality. Cornstalk was detained by the fort commander, who had decided on his own initiative to take hostage any Shawnees who fell into his hands. When, on November 10, an American militiaman from the fort was killed nearby by unknown Indians, angry soldiers brutally executed Cornstalk, his son, and two other Shawnees.

American political and military leaders were alarmed by the murder of Cornstalk; they believed he was their only hope of securing Shawnee neutrality. At the insistence of Patrick Henry, the governor of Virginia, Cornstalk?s killers (whom Henry called ?vile assassins?) were eventually brought to trial, but since their fellow soldiers would not testify against them, all were acquitted.

Cornstalk is buried in Point Pleasant. Legends arose about his dying "curse" being the cause of misfortunes in the area (later supplanted by local "mothman" stories), though no contemporary historical source mentions any such utterance by Cornstalk.

©

Ohio City Productions, Inc.

All Rights Reserved.